History of the American Bald Eagle

Continued-

Before settlers landed on American shores the population of the Bald Eagle may have eclipsed a half a million. With a range from Alaska to Mexico the majestic Eagle soared through the skies of a virgin land. As the human population increased and the natural habitat of the eagles declined the numbers of eagles plummeted by the late 1800’s. Observations were made that a bird once nearly ubiquitous in the land was now almost a memory. With that realization people came to their senses and began a progressive series of legislative acts to protect the American Bald Eagle culminating with the Bald Eagle being placed on the list of Endangered Species in 1967 and followed up with the Endangered Species Act of 1973. What followed is a success story in the restoration of the American Bald Eagle that is unfortunately exclusive to only a few species protected under the Endangered Species Act; the recovery culminated on June 28, 2007 with the delisting of the American Bald Eagle from the list. The Eagle remains protected by the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.

History of the American Bald Eagle

“The eagle is a nice bird. We like to see it – on twenty-dollar gold pieces. Sentimentally, it is a beautiful thing, but in life it is a destroyer of food and should be killed wherever found.” Douglas Island News, August 6, 1920

Such was the sentiment for the national treasure that is the American Bald Eagle in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Congress selected the American Bald Eagle as the National Symbol of the United States in 1782 for it’s majesty and it’s representation of courage and might. By the late 1800’s however, as industry grew and the appetite for consumption of natural resources for profit expanded across the west, bounties were passed on the Bald Eagle across the US and paid on eagles claws until 1953 in Alaska. Even as the Bald Eagle Protection act of June 8 1940 prohibited the taking or possession of Bald Eagles thereby eliminating the purposeful destruction of eagles, Alaska delegate Anthony J. Dimond politicked to secure an Alaska exclusion from that act. Anthony Dimond had previously been responsible for increasing the bounty on eagles in Alaska from 50 cents to one dollar and was an obvious opponent of any attempt by the federal government to abolish bounty hunting in Alaska. Dimond’s increase in the bounty paid on eagles claws effected a change in the bounty hunting industry as the higher price moved the hunting of Bald Eagles from opportunistic to professional eradication for profit. The Territory of Alaska was bent on destroying what was viewed as a competitor for Alaska’s game and domestic resources. These rich and thriving resources were dead set in the sights of large commercial interests, one of which was the fishing industry out of Washington State. The large fish canneries, having obliterated the salmon industry along the pacific coast, moved north to fish out the Alaskan waters and actively pursued anything that they might perceive to be a threat to their profitability. Bounties on eagles were paid from the territorial treasury and later the state treasury for the confirmed destruction of 120,195 American Bald Eagles. The number of additional casualties due to wounding or other collateral damage such as juveniles who lost parents are incalculable.

On Trumpeter Swans

The following is an exert from our web page Fall River Photography on Alaska Trumpeter Swans. You can read more and enjoy our collection at this link:http://www.fallriverphotography.com/t-trumpeter-swan.aspx.

Biology

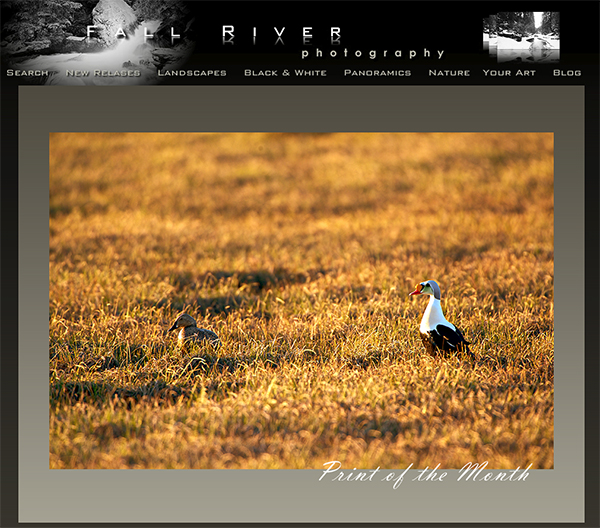

A majestic bird, the wing span of an adult Trumpeter Swan can reach in excess of 7 feet and the males, called Cobs, may weigh near 30 pounds. A Trumpeter Swan in the wild may live for 20-30 years and will usually mate for life. The breeding pair will return to the same wetlands for nesting, often using the same nest mound year after year.

The Cob and Pen (the female trumpeter swan) will build a nest mound together with the Pen pilling up the vegetation the Cob collects then creating her nest depression. After laying 5 to 9 eggs in her clutch the pen incubates the eggs for 33 days only occasionally departing the nest to feed and preen and only after covering her eggs. The nest mound is typically surrounded by water and may be as much as 6 feet high providing excellent protection from mammalian predators however, the Cob will remain on watch and vigorously defend the clutch. After the cygnets hatch they move to the water within two days to feed on vegetation and small invertebrate. Their young, called cygnets develop very quickly gaining 20% of their body weight daily and are foraging for vegetation as their parents do, with their bills, after about 4 weeks.

Shortly after the hatch a staggered molting period ensues for both adults. The Pen leads off shedding and regrowing her flight feathers on her wings and tail. The Cob follows with his molt only after the Pen has regrown her flight feathers thus ensuring there is always an adult capable of flight to defend the cygnets.

The young cygnets grow rapidly and are feathered out by the 9th or 10th week. Flight usually is not possible prior to 15 weeks of development at which time they typically weigh about 20 pounds. Flight school usually starts in September and that skill requires daily practice to make the migration flight prior to winter freeze up. The cygnets follow the adults on their first migration to the family wintering grounds learning the migratory route and winter feeding habitat. The young trumpeter swans usually remain with their brood-mates through at least the first year following their parents on the migration back to the breeding area. The young swans are then driven away by their parents but will remain together in sibling groups until reaching the age of about 2 years. Annual regrouping of trumpeter swans with their parents at the established family wintering grounds is common behavior for the offspring and strengthens the learned patterns being passed along in the lineage.

In year 3 the young trumpeter swans will select mating partners while on the wintering grounds and pair up to migrate back to the breeding areas. Unmated swans will gather in small flocks along the large lakes within their breeding grounds. Migration flights are in flocks made up of family units or comprised of several families inter mixed with non breeding swans.

Trumpeter Swans diet consists predominately of foliage, seeds and various marsh plants. Studies have shown adult trumpeter swans capable of consuming more than 20 pounds of aquatic vegetation daily. Cygnets, upon first reaching the water require a high protein diet and focus their feeding efforts on the aquatic invertebrates for the first few weeks of growth. Alaska’s high invertebrate population supports this handily. Newly introduced learned feeding patterns have provided a greater range of winter feeding habitat for the trumpeter swans. These new patterns provide for the swans to winter near agricultural fields and consume winter wheat and unharvested grains. It is notable that conflicts have arisen with farmers experiencing crop damage from roving flocks of swans but overall the swan population has benefitted from these new winter grounds.

On Trumpeter Swans

The following is an exert from our web page Fall River Photography on Alaska Trumpeter Swans. You can read more and enjoy our collection at this link:http://www.fallriverphotography.com/t-trumpeter-swan.aspx.

History

Trumpeter swans have been claiming Alaska as a breeding ground for longer than we have known they were here. Market hunting of trumpeters in the lower 48 states had decimated the species. These hunters sold Trumpeter Swans for their meat to food markets and their feathers for the millinery trade and had accomplished winnowing the population down so far as to consider Trumpeter Swans as an endangered species by the early 1900’s. By that time, the decline of the Trumpeter Swan was so precipitous that the Lacey Act of 1900 and the following Migratory Bird Act of 1929 had no ability to reverse or mitigate the decline. Another unfortunate note is that there was no legal definition of endangered species as we know it today and hence protection of the classification until 1976 so the further slide toward extinction was practically inevitable. By 1932 regardless of their status, Trumpeter Swans had been reduced to 69 wild birds. The future of the trumpeter, like so many other species that were caught up in the destruction of wildlife that the move westward produced, were on the brink of destruction. The Trumpeter Swan, a regal and majestic bird that had occupied a breeding range over most of northern America, had been brought literally to the very brink of observable extinction.

Then in 1968 an olive branch of forgiveness was extended by the forces of nature for sins of the past with the miraculous discovery of Trumpeter Swan breeding habit in Alaska. Air surveys counted 2,844 trumpeter swans in the wild that had never before been known to exist. Further efforts to better define the trumpeter swans breeding locations resulted in additional birds being found and the results of the census in 1969 allowed for the trumpeter swan to be removed from the endangered species list.

The damage to the migratory bird’s future was and actually still is severely impacted by the loss of those original migratory Trumpeter Swans. The Trumpeter Swan’s survival is based on a model of strong family bonds that pass along crucial learned patterns of behavior and habitat use. These patterns are most often passed along by older birds in the family hierarchy and it was observed that critical knowledge of wintering habitat and food sources as well as established migratory routes had been lost. The effect of this is still being seen today with biologists observing birds wintering in locations that result in very high number of winter deaths as a result of starvation.

On Trumpeter Swans

Here is an exert from our Trumpeter Swan page on our site Fall River Photography. You can read more at the this link:http://www.fallriverphotography.com/t-trumpeter-swan.aspx. It is getting to be spring in Alaska and that means trumpeter swans.

Notes From the Field

The triumphant male Trumpeter Swan lorded it over the other swans swimming in the water from the bench of ice that he was on; the message was undeniable. With his chest thrust out, wings back and extended, and that unmistakable arrogant strut, victory was announced and dominance declared.

In early spring open water is at a premium that the swans are only tenuously willing to share. The coming breeding season is approaching, so of course the swans are also restless and aggressive this time of year. The fragile powder keg of aggression in the swans on this pool only needs one thing to get out of sorts to cause it to explode and a pair of swans coming in to land on the water sets it off. An extended series of battles between swan pairs ensued that carried on back and forth across the open water. The result was several swans departured and others were sporting sore swan backsides from “goosing” but nothing of major injurious consequence, thank goodness. I can assure you the battles were fierce though, regardless of the lack of obvious wounds.